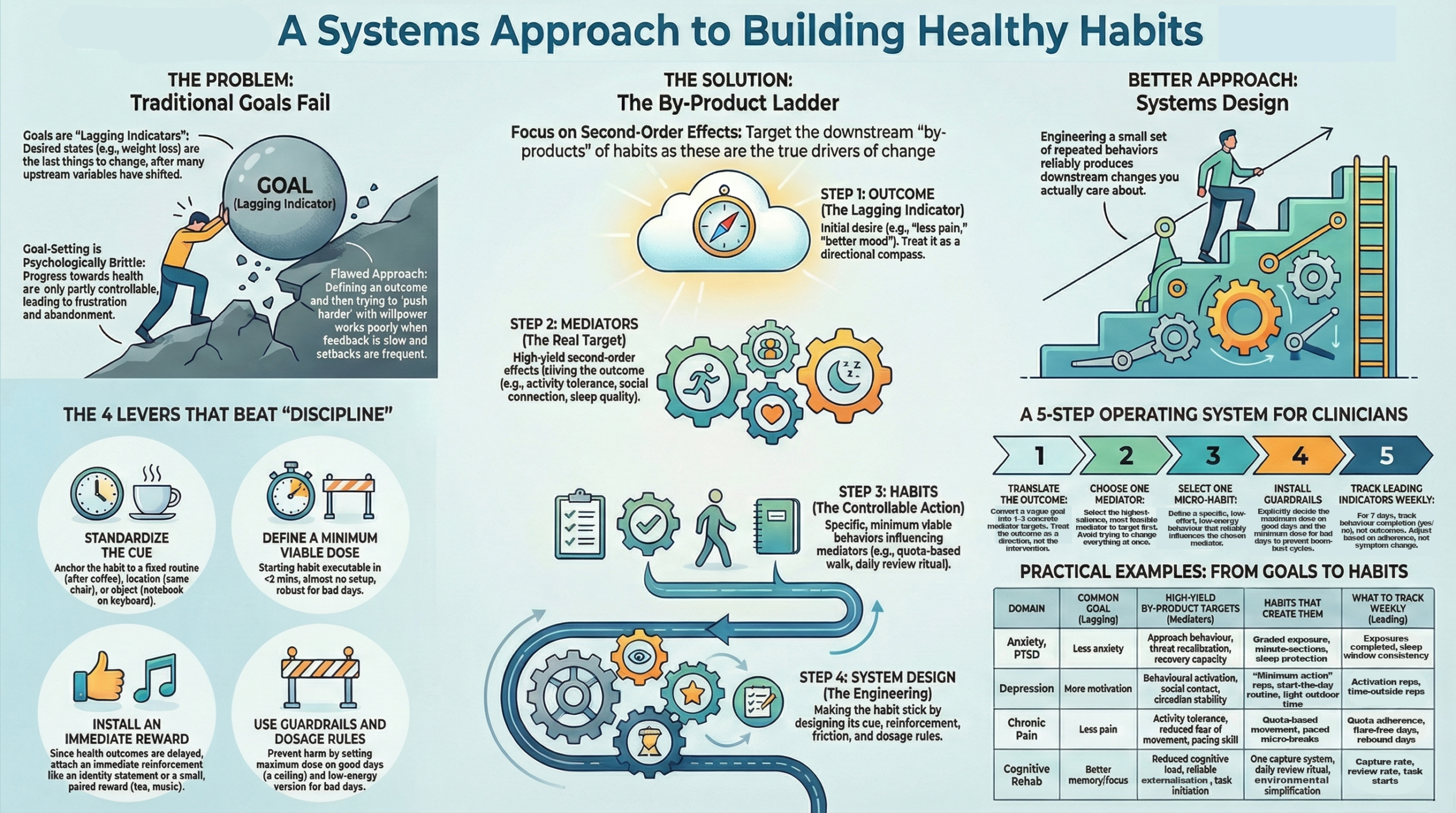

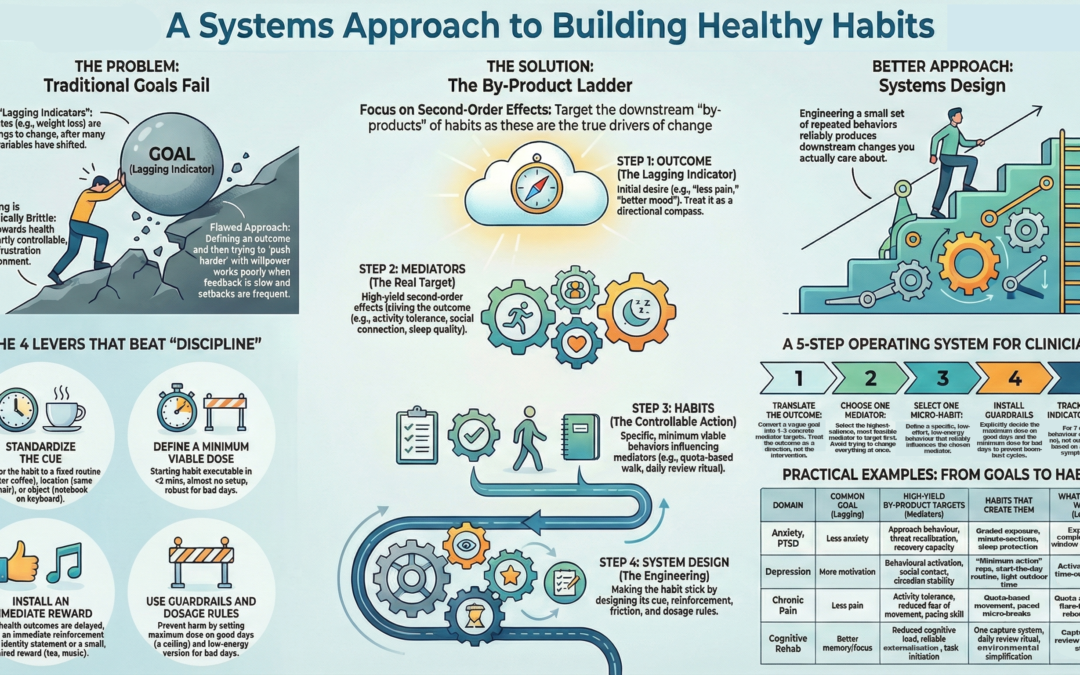

Why Habits Beat Goals in Mental Health, Rehab, and Chronic Pain

Most people are taught to improve their health by setting better goals.

Less anxiety.

Less pain.

More motivation.

Better focus.

A return to “normal.”

In healthcare, mental health, and rehabilitation, this approach routinely fails. Not because the goals are wrong, but because goals are lagging indicators. They move last, after many upstream variables have already shifted. When people aim directly at outcomes they cannot fully control, they often experience frustration, inconsistency, and self-blame.

There is a better way to think about change. It focuses on second-order effects. Instead of asking “What do I want?”, it asks “What conditions reliably produce the kind of change I want, even when motivation fluctuates?”

First-order goals vs second-order effects

A first-order goal is an outcome you care about. Reduced anxiety. Improved mood. Fewer pain flares. Better memory.

A second-order effect is a downstream change that emerges when behaviour interacts with the nervous system and environment over time. Examples include:

- Reduced avoidance

- Improved recovery after stress

- Greater predictability in daily capacity

- Increased confidence in pacing

- Lower cognitive load

- Improved sleep regularity

These second-order effects are rarely the goals people name. Yet they are often the true drivers of improvement.

In complex biological systems, outcomes are not imposed. They emerge when the appropriate upstream variables stabilize.

Why goal-chasing breaks down in health contexts

Goal-based thinking works best when feedback is fast and linear. Health is neither.

Consider anxiety. If someone sets a goal to “feel less anxious,” they immediately run into three problems:

- Anxiety fluctuates naturally.

- Effort does not reliably reduce it in the moment.

- Monitoring anxiety often increases anxiety.

The same pattern appears in chronic pain, depression, and cognitive rehabilitation. People work hard, see inconsistent results, and conclude that something is wrong with them.

The problem is not effort. It is target selection.

When goals are treated as operational targets rather than directional markers, people end up fighting the system within which they operate.

A systems alternative: the By-Product Ladder

A more reliable approach is to work backward from outcomes to the variables that actually move them.

This can be expressed as a simple ladder:

Outcome → Mediators → Mechanisms → Habits → System Design

Outcomes are what people care about.

Mediators are second-order variables that cause changes in outcomes.

Mechanisms explain why those mediators matter.

Habits are the repeated behaviours that activate the mechanisms.

System design determines whether the habits actually install.

The critical move is to shift attention from outcomes to mediators. Mediators are controllable. Outcomes are not.

Example 1: Anxiety and avoidance

The usual goal

“Reduce anxiety.”

The real drivers

Anxiety decreases over time when:

- Avoidance decreases.

- Safety behaviours are reduced.

- Recovery after arousal improves.

These are second-order effects. They do not feel like progress at first. In fact, they often feel worse before they feel better.

The mechanism

Repeated, tolerable exposure creates new learning. The nervous system updates its predictions. Arousal becomes less threatening. Recovery becomes faster.

The habits

- A brief daily exposure micro-session.

- Gradual reduction of one safety behaviour.

- A short, non-analytical post-exposure downshift.

None of these habits aims at anxiety reduction directly. Anxiety reduction emerges as a by-product of a consistent approach and recovery.

Why this works

The person is no longer asking, “Do I feel better?”

They are asking, “Did I approach, and did I recover?”

That shift alone often restores a sense of control.

Example 2: Chronic pain and pacing

The usual goal: “Reduce pain.”

The real drivers

Function improves when:

- Activity becomes predictable.

- Fear of movement decreases.

- Capacity is dosed consistently.

Pain intensity often lags behind these changes.

The mechanism: Graded exposure and predictable loading reduce sensitization. The nervous system relearns that movement is survivable. Confidence grows through consistency, not intensity.

The habits

- A fixed daily movement quota, below the flare threshold.

- Timed micro-breaks that redistribute load.

- A written flare plan that preserves continuity.

These habits deliberately avoid symptom-based decision-making. They are quota-based, not feeling-based.

Why this works: The person stops oscillating between overdoing and shutting down. Predictability increases. Confidence follows. Pain becomes less dominant, even if it does not disappear.

Why habits matter more than discipline: People often misinterpret consistent behaviour as discipline. In reality, discipline is primarily required at the outset. What sustains change is habit installation.

A habit is not just repetition. It is a behaviour that:

- Fires in response to a stable cue.

- Has low friction to start.

- Has a clearly defined completion boundary.

- Is reinforced immediately, not eventually.

Most failed behaviour change in healthcare is not due to a lack of motivation. It is due to poor system design.

When people are asked to rely on willpower in the presence of pain, fatigue, anxiety, or cognitive overload, failure is predictable.

Guardrails matter because second-order effects can cut both ways

Second-order thinking cuts in both directions. Poorly designed habits can produce harmful by-products:

- Overexposure leading to burnout.

- Overexercise leading to flares.

- Excessive symptom monitoring increases distress.

- Rigid routines are becoming punitive.

This is why dosage rules and ceilings matter. More is not better. Consistency is better.

In health contexts, the safest habit is the one that still gets done on bad days.

What to track instead of outcomes: If outcomes are lagging indicators, they should not be tracked daily.

Better daily indicators include:

- Was the habit completed?

- Was avoidance reduced?

- Was recovery supported?

- Was the quota respected?

Outcomes are reviewed weekly or monthly, not hourly. This protects people from misinterpreting normal variability as failure.

The deeper shift

This approach requires a conceptual shift:

Stop asking, “How do I get what I want?”

Start asking, “What conditions reliably produce what I want, even when I feel off?”

In healthcare, mental health, and rehabilitation, progress is rarely dramatic. It is structural. It happens when the system becomes more stable, more predictable, and more forgiving. Goals still matter. But they belong at the top of the ladder, not at the centre of daily life.

If you build the right by-products, the outcomes tend to follow.

Recent Comments